Courtesy of Birmingham Royal Ballet ©. (Click image for larger version)

www.brb.org.uk

www.elmhurstdance.co.uk

Desmond Kelly, who retires this week as Artistic Director of Elmhurst School for Dance, has been part of the British ballet scene and the various Royal Ballet organisations for so long that it seems he’s always been here. Not so: he was born in Zimbabwe, and already had a varied career behind him when he joined the Royal Ballet.

We talked in his office, in the very pleasant, light surroundings of Elmhurst, and began with how he came to start learning ballet.

The apprentice

As happens so often when you ask a male dancer that question, his answer starts ‘Well, my sister…’

‘Well, my sister actually started. She and I are very close – in fact she lives in Birmingham now – and it sort of took her away from me, and I thought “Hm, I might try that“. I hated it to start with and my mother used to bribe me to go – she used to buy me a Dinky toy each time I did a lesson. Elaine Archibald, my teacher, said “He’s got the right shape, he should be all right”, and slowly I got hooked on it. When I discovered that because of my dance I was actually better at sports than most of the boys at my school – I could jump higher than them, and longer – I thought “Maybe there’s something in this”; it was insidious, it slowly crept into my psyche until eventually I couldn’t do without it.’

Elaine Archibald was one of the best-known teachers in Zimbabwe, and produced several dancers who later made careers in British companies. She had a thriving school – Kelly was one of 3 boys among about 200 girls – but there was no opportunity to become professional in that country, and at the age of 16 he won an RAD scholarship to come to London. There he joined the school run by Ruth French, who had been one of Pavlova’s dancers before joining the Vic-Wells Ballet, where she’s best remembered for having danced Odile to Fonteyn’s first Odette.

‘It was a small school, in a church hall – unheated, and with a hard parquet floor. I was there for about nine months, until I auditioned for Festival Ballet. Anton Dolin was running the company in those days. They needed a couple of boys, and Ben Stevenson [later director of the Houston Ballet and Texas Ballet Theater] and I auditioned on the same day – he got a full contract and I got an apprentice contract, for which I was paid £10.10s a week. Not bad for those days.’

The dancer

Desmond joined Festival Ballet in 1959 and was promoted to soloist three years later. He was given some good roles early on, and when Dance & Dancers featured him in their monthly ‘dancer you will know’ series, John Percival wrote:

‘To be cast at only 21 in the male role in Le Spectre de la Rose and Les Sylphides is rather like learning to swim by jumping in at the deep end. The wonder is not that Desmond Kelly, when he first tackled these parts, was less than perfect, but that he survived at all and went on to work up his performance in Les Sylphides, in a remarkably short time, into something very presentable. Gone is a rather mannered bearing he showed at first; remaining is a cool, reserved elegance. Kelly’s strong, easy dancing and partnering in Etudes, as much as any of the bigger parts he has so far taken in London, gives clear promise of his future.’

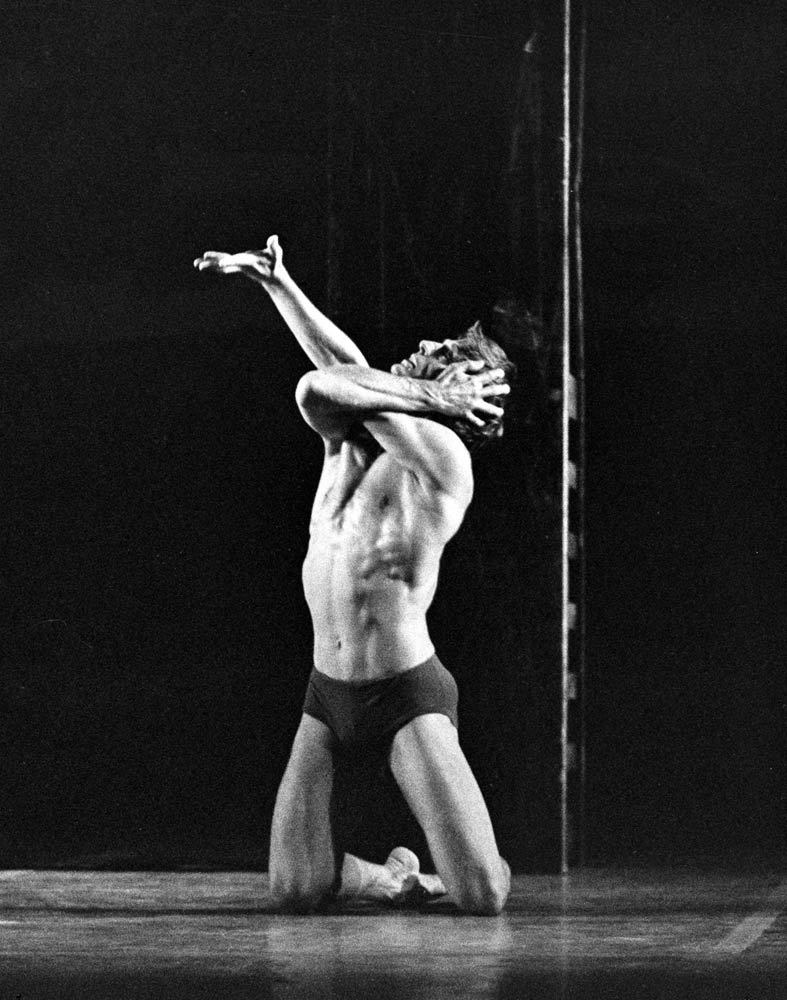

© Bill Cooper and courtesy of Birmingham Royal Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

‘Cool, reserved elegance’ fits well with my memories of Kelly later in his career: he was the danseur noble type but a strong rather than a lyrical dancer – Dorkon rather than Daphnis when it came to Daphnis and Chloe. He was soon promoted to principal in Festival Ballet, and around the same time he married a colleague from the company, Denise le Comte.

‘We left soon after Denise and I got married – there was a big mix-up with Festival Ballet, with the directorship, and we thought we should seek horizons new. We went to Zimbabwe to start with, and while we were there UDI was declared, and most countries said they would not accept Zimbabwean passports. We were on our way to New Zealand, which made it really difficult – so I ended up by going on the train to Salisbury and banging on the door of the British consulate, and saying “Please may I have a British passport?“ And they actually gave me one, so I was able to travel. So we did go to New Zealand for a short time. Then we came back to Zurich, and worked with Papa Beriosoff, and from there we went back to NZ and were there for about 18 months.’

Was this part of a long term plan?

‘No, we were just drifting – ‘seeking’ is the word – trying to find somewhere. While we were in NZ on the second stint, I was being ballet master and teaching and dancing, and it was proving a little too much – I just wanted to dance at that stage – and then I got a cable from the company in Washington, the Washington National Ballet, saying would I come and partner Gaye Fulton, who I’d previously danced with in ENB – and I accepted with alacrity. Then I think I was there for two seasons, Dancing with Margot – that’s when I first danced with Margot, when I was with Washington Ballet. [They danced Bournonville’s La Sylphide together, among other things.] And it was she who suggested that I should audition for the Royal Ballet. So we both auditioned. Denise was pregnant at the time but we didn’t tell them – because we needed the money and they wouldn’t accept pregnant women. She was very flat, fortunately! – so she joined with me. In fact I joined the touring company, just before it disbanded.’

© Leslie E. Spatt and courtesy of Birmingham Royal Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

Kelly arrived at a turning point for the touring section of the Royal Ballet – in fact he’d only been there for three months when he found himself dancing in the company’s last performance, replacing the injured David Wall as Siegfried in Swan Lake, with the very popular Doreen Wells as Odette/Odile. Fortunately, though, that did mean he had at least a short time under the directorship of John Field, who was famous for the care with which he developed his dancers.

‘John was marvellous to me, just marvellous – he encouraged me, nurtured me, made me feel I was actually worth being in the Royal Ballet. He really took me under his wing – even years later, when he’d left and become director of the ballet at La Scala, he invited me to come to Italy and I danced some guest performances there.’

In those days it was quite unusual for a dancer to join at principal level from another company – I don’t remember it happening again until Jay Jolley arrived in the 1980s – and I wondered if it caused any resentment.

‘Not resentment, no, but I felt like an outsider for nearly 10 years. Not just because I was the new boy, but because my background was so different, my training was so different – and it was something that hadn’t happened all that much, having people from the outside – they actually called it ‘the outside’.

Four months after the touring section closed, it was reborn as the New Group – a much smaller ensemble, the idea being that it would show more new work; it’s first programme included a piece that was to have a huge effect both on the company and on Kelly himself.

Field Figures

Glen Tetley was invited to make a work for the new group – a complete break with tradition. Jann Parry’s obituary of Tetley tells of his claim that he had a very difficult time with the Royal Ballet and decided that he would give the leading roles in Field Figures to the first dancers to actually smile at him, who turned out to be Kelly and Deanne Bergsma. True story?

‘I don’t like to think so – I’d rather think that Glen came in and looked round and said [gasp] “HIM! And HER!” But in any case he met no resistance from the cast he chose, we absolutely accepted him. Perhaps at some level there were people who saw him as breaking tradition – they were so isolated as a classical ballet company – but I don’t remember any resentment with Glen, especially after he’d been there for a while, because he was such a wonderful guy, a fantastic character, someone we respected deeply.

‘We trained with him for about 3 months. It’s quite different, the way that he worked, it’s much more grounded and centralised – instead of elevation and elongation and stretching out, it’s the opposite. I remember being so exhausted after every rehearsal – Glen had this thing about the human body being very beautiful in a state of exhaustion – he used to love it when we were completely knackered – he said “then your true self comes out”.’

Would you say that he made an impact comparable with the arrival of Wayne McGregor, 30 years later? Was it that sort of leap into the future?

‘I think it probably was, yes. Because they hadn’t done anything like that before, ever. The Stockhausen music – forty minutes long – used to drive people crazy. In fact years later, when we toured the ballet and we went to Stratford, people asked for their money back, because they said this was not ballet.’

How hard was it to learn this new style at the same time as dancing the standard repertory?

‘Very hard – hard as hell. I have a heart condition now – my heart has developed more on one side than the other – and I often wonder if it’s the extreme exhaustion of many of the ballets I did, like Giselle and Glen’s stuff. It’s different with athletes, because they have such prolonged sessions, and ours come in such short bursts – that point of exhaustion – and I often wonder if maybe this happened because of dance. But if it did, I don’t regret it at all.

‘It’s a kind of a sacrifice, I suppose, because our bodies are our instrument – so using that instrument to the nth degree is part of the satisfaction, is it not? – part of art.’

Back to the classics

From the New Group, Kelly was taken into the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden.

‘I don’t know what happened, but I was very lucky – I don’t know if it was Margot’s influence, or whether John had a say, but ending up in the Royal Ballet after being in the touring group was quite something for me.

‘But I wasn’t happy in the Royal Ballet because there were so many of us, and a hierarchy – those who had been there the longest got the first performances, and then they sort of went down the line, and because I was the new boy, from the outside, I didn’t get that much opportunity.’

But I remember you dancing quite a wide range of roles – not just Princes – Ballet Imperial, Four Temperaments, Lescaut in Manon, Monotones, Romeo…

‘Yes, I did Apollo, and contemporary stuff…but I couldn’t stand it because I wasn’t dancing enough – you’d get a class and maybe a rehearsal and occasionally a performance, but I really wasn’t dancing. I wanted to dance, to be dancing every day, so I asked to go back to the touring company…’

…which by then had become the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, under the direction of Peter Wright. My chief memory of Kelly at that time is of seeing him in David Bintley’s Metamorphosis – he and Margaret Barbieri were cast as Gregor’s parents and it was a real shock to see these two elegant classical dancers in dowdy cardigans and straggly grey hair. Kelly has portrayed lots of what he refers to as ‘old gents’ since then but none so depressed and depressing.

© Leslie E. Spatt and courtesy of Birmingham Royal Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

His last performance as a principal was as the Prodigal Son. How did it feel, to know that was the one?

‘It felt… wonderful. I know that a lot of dancers go through a sort of mourning period when they stop – they feel regret, and nostalgia – but I was very lucky because Peter Wright had encouraged me to teach and rehearse and coach, and I found it almost more satisfying than dancing – I felt at that stage that I had danced to teach. I have never ever, thank God, looked at a dancer on stage and thought “I could do that better” or “I wish I was still doing that“. It was an absolute cut-off. ’

Had you got from it what you needed – not just that you were tired of the tights and the pliés and stuff?

‘No, I’d drunk the whole glass – I felt “now I’m teaching, now I’m doing what I’ve always wanted to do” – and I thank Peter [Wright] so much for it. And I’ve now I’ve been teaching for 30 years or something, and I’ve never regretted becoming a teacher.’

Ballet Hoo!

In 1990 Kelly was appointed Assistant Director of what by then was the Birmingham Royal Ballet, and became known internationally as well as at home for his coaching, teaching and staging. If my own one glimpse of him as a coach is typical, his high reputation is very well deserved: at the Fonteyn Conference in 1999 I saw him transform Belinda Hatley’s Aurora from very nice to beautiful just by suggesting that she should take a breath at a different moment. His staging of Ashton’s Enigma Variations was particularly admired.

© Bill Cooper and courtesy of Birmingham Royal Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

Outside the ballet world, though, his name is most closely associated with the 2006 television series Ballet Hoo!, which took a group of young people with no dance background and turned them into a team capable of performing all but the leading roles in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet. He was quite surprised when I mentioned this as one of his most memorable achievements:

‘Do you think it made that much impression? We didn’t have that big an audience… but it certainly had a huge impact on me, I know that – it changed me. My nickname in BRB used to be Bastard – and something happened with Ballet Hoo! – I don’t know whether it’s my age, or the kids we worked with, but it made me realise that you can get the best out of dancers and students by coming in on a certain level and talking to them on a certain level – not always shouting. I do shout still, I do get very angry – I did yesterday with our kids who are doing Les Rendezvous, yelling that they were NOT UP TO SCRATCH – but it helped to mellow me, and I realised so many things. I hope it made me a better person, being confronted by these kids, who came from dreadful backgrounds, and still managed to survive, to come all the way through the process of Romeo and Juliet – they were just amazing kids, amazing.’

Courtesy of Birmingham Royal Ballet ©. (Click image for larger version)

Was it alarming for you, when you first went into it?

‘Marion [Tait] and I went into it with closed eyes – we didn’t know what to expect. I wasn’t frightened, because when we first went into schools, I took half-a-dozen dancers with me and we did some of The Upper Room, because I didn’t want to do classical ballet, and they took to it – at the end of each session they were actually on the stage learning the choreography. And I thought “well, if we can get this channelled into Romeo and Juliet there won’t be any problem“. But in fact there were many problems, because of course these kids were not used to discipline, getting up at 7 or 8 o’clock in the morning, finding their way – in the end, you know, we had to get taxis for a lot of them. And also food was a huge problem, because they didn’t have any money – they didn’t eat: so taxis and breakfast was the beginning of their day, and then a set period for lunch, and decent food. Great things have happened to the kids since then.’

Do you keep in touch with them?

‘Yes, with Lyndon in particular, the guy that did Tybalt: he’s just graduating this year from acting school – he’s had some good reviews and I think he’ll probably make it as an actor.’

© Phil Hitchman and courtesy of Birmingham Royal Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

Kelly may not have registered the full impact of the series, but BRB’s PR Manager, Simon Harper, told me that six years later he still gets far more requests for information about it than about anything else their outreach department has done.

Elmhurst

In 2008 Kelly retired from BRB and joined the Elmhurst School as its Artistic Director. Although he’s clearly got a lot from his four years in the job, he’s handing over to Robert Parker with some ambitions for the school still unfulfilled. His line manager is Jessica Ward, the school’s Principal, but…

‘I don’t think of her as being my boss – I think of her as being the overall academic person, and I consider this role, whoever does it, as being equal to that: because this is a dance school. I know our education side is very important, and also very successful, but children do not come into the school to become academics, they come here to become dancers, and that’s what I think tends to be forgotten, and pushed under the carpet a bit. I hope Robert will forge ahead and make the dance in the school even more important. Of course I recognise, being a father and a grandfather, how important it is to have an education – especially in these times when jobs are not easy to find – and when kids leave here at 18, if they have 2 A levels and their diploma under their belts, they can do 12 months external study and get an MA . But in fact we work around the academics, and I want it so the academics work around us. Robert’s very conscious of that, because he’s been round two or three schools on the continent – Paris Opera, Hamburg, places like that – and there, the dance comes first, the academics slots in.’

Do you think that’s because the ones you mention have always been direct feeder schools for their company?

‘Yes, I think that’s got a lot to do with it. But over the years I hope that the stature of Elmhurst will change. The teaching quality here is phenomenal – I’ve been really bowled over by the expertise of the teachers. The talent intake is already changing – when I go and look at years 7, 8, 9 and 10, there are some really talented kids there, seriously talented, and when that works through, and we get a real reputation for producing top-class classical dancers, who can also turn their hand to contemporary or jazz or whatever, and we become the recognised feeder school for BRB – we already have five Elmhurst dancers in the company – then the status will change.

‘But I want Elmhurst to be on an equal footing with the Royal Ballet School so that we don’t have the problem of losing some of our most talented kids to them. It’s partly because of funding: the RBS can offer all their students full MDS (Music and Dance Scheme) funding whilst we have only a limited number of MDS places and can only offer DaDa (Dance and Drama Awards) funding to most of our students, so we get talented kids moving into the upper school – and if you were offered a DaDa here or MDS there, which would you take? – you’d take the MDS of course. I hope in these difficult times that we’ll at least retain the MDS numbers we have, but I’d really like it to be enough to cover the whole school.’

Given the enthusiasm he’d expressed for teaching, I was quite surprised to hear that he’s done very little in his time at the school.

‘I’ve taught possibly half-a-dozen times in the 4 years – because of this [points at paper-covered desk] and that’s one of the reasons why I’m not really regretting leaving the school. I’m very good person-to-person, I can deal with the students really well, but I want to deal with them even more, I want to be in the rehearsal room, to be there teaching and coaching, and teaching ballet . Instead I‘m sitting here for 10 hours a day writing reports and all that stuff – that’s an admin job and I’m not an administrator at all.

‘I’ve been trying to persuade Robert to actually teach – don’t forget he’s half my age, with as much energy as I’ve got. He’s actually going to take care of a year-group – he’s going to teach the 6.1 Men, the 16-year-olds, as their principal teacher. So whatever happens here, he’s going to have to find time to go out there.’

Looking back, looking forward

If you look back at your own training in Zimbabwe and with Ruth French, and then at what students get these days, what have they got, going into a company at 18, that you didn’t have?

‘They have much, much stronger techniques now; the technical requirements expected of dancers these days have gone way up, way up – when you see some of the Cuban boys, they are phenomenal. We didn’t have techniques like that. But we had something else – we had what I consider to be really important – because you must have to have your technique to start with, but it can’t be dominant, your technique can’t be everything: you have to be able to have a personality, to act, to be able to see yourself through 4 acts of a ballet and convince the public that you are that person. That kind of artistry has become less important now, although there are still certain dancers that have it naturally, but it’s not general.’

How do you see the future? In 50 years time will there still be people who can, for instance, coach Ashton properly?

‘I think so, looking at people like Robert Parker, who I’ve coached in certain roles – there will come a time when he will pass it on to the next generation. I don’t know if over the years it will become diluted – I don’t know how fiercely people think about it. I’m very fierce about things like Ashton’s styling, and Kenneth’s styling – you know, keeping the difference of style. But I do think that the classical styles are becoming less distinct. I mean 50 years ago the English style was quite distinctive, the American style was quite distinctive, Russian, French… now, because they’re all doing the same ballets, they’re becoming the same dancers.’

And what’s next for you?

‘Well, I still have a very close association with David and the company, and he’s asked me to go to Japan in January to stage his Giselle, and I hope, while I’ve still got a little energy and my health, that I’ll do more of that. I’d love to go back into the company occasionally and teach class, and if there’s any coaching to be done, I’d love to do that too.

I don’t want to do too much, though – I’ve done it for 50-something years and I’d like to have a little time with Denise, and with my kids and the grandkids. They live in London which is only a couple of hours away, but they’ve got their lives and their schools and their jobs to attend to – if I have the freedom to go down there it will be much better. And I’m also a very keen gardener – I have a huge allotment, which I don’t see often enough – it’s in the evenings and at weekends at present. People are quite impressed, actually, because Denise and I – even at our advanced age – have dug the whole thing. We grow all our own vegetables for the whole summer.’

Looking back over your career, tell me the highlights – the things you’re most proud of, or the things you most enjoyed…

‘That’s a really difficult question, because I’ve enjoyed every single moment of it. Dancing with Margot, is that a highlight? I dropped her once, in the Berlioz Romeo and Juliet, actually dropped her on her knees in a rehearsal, and she made such a fuss, she was sobbing and groaning, and I thought ‘Desmond, that’s the end of your career’, and then she suddenly looked up at me and said, “My knees haven’t felt this good for years!” – she was kidding me the whole time. She was always laughing, Margot – people always forget – she had this brimming laughter, she loved a joke, she loved to laugh all day. So dancing with her was a real highlight. Joining the Royal Ballet was a highlight, getting my first job, with Anton Dolin, was a highlight, going to New Zealand was a highlight, becoming a ballet master, teaching – everything, everything.

‘But it’s not finished yet, Jane. I can’t give it up, I can’t – it’s a drug, it’s a necessary part of life, some connection with the dance world. I was talking to Monica Mason the other day and she said, “Darling, we won’t ever stop, we’ll always be doing something”, and it’s perfectly true.

‘I have been so fortunate to have a mentor like Peter Wright – without him I would never have made this part of my career: what I would most like is that one day someone else will say the same thing about me.’

You must be logged in to post a comment.