Swan Lake at ABT: Farewells and Débuts

American Ballet Theatre

Swan Lake

New York, Metropolitan Opera House

27 and 28 June 2012

abt.org

It’s that time again, the final stretch of the season, the time of farewells. At ABT, retiring dancers often choose to take their leave with one last “Swan Lake.” Last year, it was José Manuel Carreño, of the Cheshire grin and flamboyant pirouettes, who took his leave. (Michele Wiles also quietly departed, without fanfare, after a final Swan.) On June 28, Ángel Corella, one of the warmest, most joyous dancers who has ever graced the stage of the Met, performed for the last time with the company he joined back in 1995 after being discovered by Natalia Makarova. His first performance here, a rapturous memory for many a dance lover, was a “Don Quixote” with Paloma Herrera. Now, he will go off to lead his new company, Barcelona Ballet, fulltime. Next week (July 7), it will be Ethan Stiefel’s turn, though he has chosen the more playful role of Ali in “Le Corsaire” for his final hurrah. And as they depart, others arrive. This week marked the débuts of Isabella Boylston and Daniil Simkin, also in “Swan Lake,” at the Wednesday (June 27) matinée.

The production, created by Kevin McKenzie in 2000, has not improved over time. An interpolated opening sequence, performed during Tchaikovsky’s overture, consists of a creepy mime scene in which a young girl in a flowing dress is lured and then captured by a handsome older man; as she struggles in his arms, I can’t help but think of Giambologna’s “Rape of the Sabine Women,” and the promise of sexual violence. The underlying message is that sex enslaves women, and it is reiterated in the third act when the preposterously purple-clad seducer enters the court and entices the princesses one by one, even catching the Queen’s eye with a sexy Russian number that has become one of Marcelo Gomes’s greatest portraits of camp ardor. The birthday celebration with which the ballet opens is pretty enough, but dull, filled with lifeless dances and no sense of grandeur or revelry. The final lakeside act has been cut down to almost nothing. As usual at ABT, the tempi are glacial, sapping energy from the group dances and turning demonstrations of bravura into dry exercises in technique. (Nevertheless, at the June 27 matinée, Hee Seo stood out in the first act pas de trois, her jumps lingering in the air for just an extra moment.) For one thing we can be thankful: The solo violinist, who plays such a crucial role in Tchaikovsky’s score, has improved dramatically, or been replaced, since opening night. At both the June 27 matinée and the evening performance on June 28th, he or she played with great flair and flawless tone. What a difference that makes.

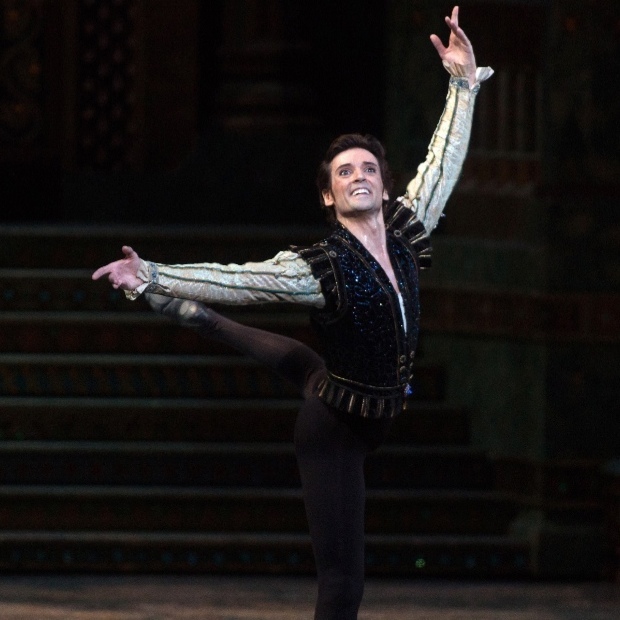

Corella’s final performance alongside Paloma Herrera – theirs is an enduring partnership – was just as one would have imagined it: ardent, joyful, and full of charm. He gave and gave, but always at the service of the greater good. This evening was about him, but it was also about his love for the company and his audience. As he appeared onstage, there was a loud roar; he looked out into the vast Met, clearly drinking it all in and thinking: “this is the last time.” Throughout the night, one caught him looking out, usually up toward the top rings at his most faithful, devoted fans. His large eyes caught the light, giving off that special spark for which he is famous. The sense of wonder, like his youthful looks, is intact. (In fact, he’s only thirty-six.)

But he also threw himself into the performance, interacting with every dancer onstage as if they were the most important person in the world to him at that moment. In the lakeside scene, he stared at Herrera’s hands as if he had never seen such hands before. (Herrera danced impeccably, with great attention to style, but seemed intent on containing her emotions. She was not going to let a farewell get in the way of an immaculate performance.) When, in the third act, Herrera returned as the impostor Odile, Corella’s face immediately lit up. But he also found complexities in his character – a shadow of doubt clouded his eyes, as he battled between his attraction for Odile and his sense that something was just not right. He hesitated for a moment before swearing his love to the comely stranger. But by the final scene, the man underneath was beginning to supplant the character. Corella’s final embrace of Odette was that of a loving brother and partner: “I’ll miss you so much!” he was telling Herrera, the woman. His parting leap was no spectacular swan dive, but a simple exit, over the cliff and into his new life. He knew it was time to go, and he did with the grace and modesty for which he is loved.

His curtain calls were equally generous. As ballerinas and male colleagues filed in, one after the other, bearing bouquets and kisses, and the audience showered him with yet more flowers and adoration, Corella looked happy but slightly embarrassed at all the fuss. Because the audience begged, he did a final series of turns à la seconde, but there was nothing showy about this gesture. The simplicity of his demeanor, the ardor in his eyes, is what people will remember most about him, even more than the crazy spins and musically precise, clean landings.

Stage demeanor is such an important part of what binds the audience to a dancer. Who is this person? It is what one looks for in any newcomer beginning to make his or her way up the ranks. At the Wednesday matinée, the audience got its first peek at two young dancers in their first “Swan Lake”: Isabella Boylston and Daniil Simkin. Both have been steadily acquiring new roles; Boylston was one of the dancers selected by Alexei Ratmansky for his new “Firebird,” and last year she performed the role of the Ballerina in “The Bright Stream.” She has an air of mystery about her, and lush, musical approach to the steps. Simkin is very different: light, brilliant, extraordinarily gifted and self-assured, but lacking in gravitas or depth. He’s a great Benvolio in “Romeo and Juliet,” where he can play the scamp, but so far, nobility and real sensitivity have eluded him. The closest he has come was in Antony Tudor’s strange neo-primitivist ballet “Shadowplay,” in which he played the role of “Boy with Matted Hair.” He took the part seriously, and it brought out a more focused, less showy side of his dancing – besides which, there were no jumps to show off in. In the past, his partnering has ben less than assured, due partly to his slight physique.

I’m happy to report that their débuts in “Swan Lake” went off without a hitch. Boylston has the makings of a great Odette; there is an epic scale to her dancing, a sense of weightedness and struggle. I was struck by how she used her fingers in the lakeside act – fanned out, like feathers. More importantly, she “sings” with her body, using the steps and port de bras as part of a continuous melody, digging into the movement with her shoulders and back. She swims through space. Like Michele Wiles – an unsung Odette – she doesn’t really act with her face – but communicates emotion through phrasing, a sense of physical courage, and texture. It’s an approach that hits you on a visceral level.

Simkin has further to go in his interpretation. One the one hand, the technical aspects of the role present no real challenge. His partnering here was unproblematic, a big step forward for him. His jumps were buoyant and soaring and seemed to hover in the air, and his turns were perfectly controlled, allowing the audience to see each transition with absolute clarity, almost as if it were all happening in slow-motion. He’s impressive, for sure. But as yet, he hasn’t found his inner prince, though one could see he was trying. It’s the curse of the small-boned, sprightly male dancer. He’s young, of course, and has time to grow.

You must be logged in to post a comment.