Recreating the World Of 1923

A Post-War Cubist Collage Returns to the Stage

Relevent Links…

www.hodsonarcher.com

www.ballet-de-lorraine.com

KVS Festival

La Création du Monde on Wikipedia

Ballets Suédois on Wikipedia

Book: ‘Rolf de Mare’ by Erik Naslund reviewed by Graham Watts

Hodson & Archer Links

[/aside] [aside] www.hodsonarcher.com[/aside] [aside] Thoughts on

documentary on Hodson & Archer’s reconstruction of a lost Ballets Russes work.

[/aside] [aside] ‘Reading the Riot Act‘

Archer and Hodson on the Ups & Downs of a TV Docudrama on The Rite of Spring (February 2006)

[/aside] [aside] ‘Sacre in Kobe‘

Hans Rinderknecht’s diary and photographs of seeing Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer put Sacre on in Japan (Autumn 2005)

[/aside] [aside] ‘Seven Days from Several Months at the Mariinsky‘

In 2003 Kenneth Archer and Millicent Hodson kept a diary for Ballet.co during their staging of The Rite of Spring with the Kirov in St Petersburg.

[/aside] [aside] From 2002

Millicent Hodson Interview

[/aside]

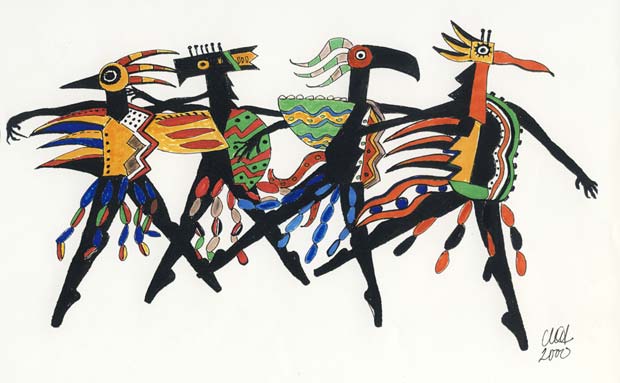

On 24 May CCN Ballet de Lorraine of Nancy will premiere “La Création du Monde, 1923-2012” for the KVS Festival in Brussels. Our re-creation of the original Ballets Suédois production is the centrepiece for a new work by Congolese choreographer, Faustin Linyekula. The 1923 collaborators called their project a “ballet nègre”. What did that term mean in 1923? What did the original artists hope to achieve in this short ballet? Seismic shifts in perception have occurred since the 1920’s in art and society, not least in terms of post-colonial questions of identity throughout Africa and the Middle East. Vast topics. In the field of the performing arts, Black dance in a myriad of styles has established itself worldwide. Does Création du Monde figure somewhere in this history? Another big subject. But our article must be brief, a sketch of this lost ballet and our effort to recreate it. We ask two basic questions: How did the world look at Création in 1923? And how did its collaborators look at their world? Linyekula’s version (music, Fabrizio Cassol; design concept, Jean-Christophe Lanquetin; costumes, Lamine Badian Kouyaté), will raise its own questions from the perspective of the present.

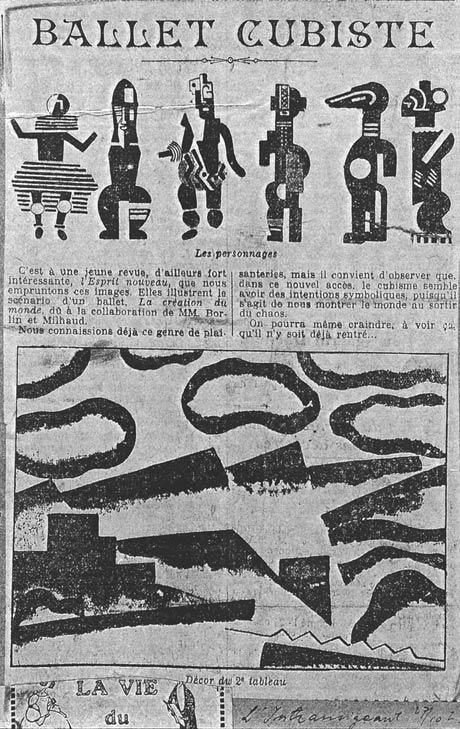

I. The Second Creation of the World

The 1923 ballet was based on the fantasized “légende des origines” by the poet, Blaise Cendrars, drawn from his Anthologie Nègre of 1919, a collection of tales recalled by missionaries and other travellers in Africa. For Cendrars, his text was a literary task of translation and interpretation. Fernand Léger, who designed La Création, came late to the Cubist practice of using African and Oceanic antiquities as models for modernism. His fascination was more focused on urban landscapes, industrial images and mechanical movement. But Création put these through the prism of myth and what was then known as “l’art nègre”. The ballet’s avant-jazz score by Darius Milhaud rang more of Harlem and Rio de Janeiro, where the composer had just travelled, than any ports of call on the African continent. Milhaud shaped these sources through techniques of contemporary music and drew upon Hebraic chants, familiar from his childhood, to evoke the simple solemnity of mankind’s first days on earth.

Rolf de Maré produced the spectacle with his Parisian company of dancers who left the Royal Swedish Ballet, en masse, to out-vanguard Diaghilev. The Ballets Suédois was really defined by the French capital, with headquarters at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, despite frequent touring throughout Europe and the U.S. during its short life from 1920-1925. Jean Börlin was the company’s star and choreographer. His eclectic style reached its zenith in La Création, combining dance fads of the day to propose a primal grammar of movement. All these diverse elements joined in La Création du Monde to form a Cubist collage of Paris in the years just after World War I.

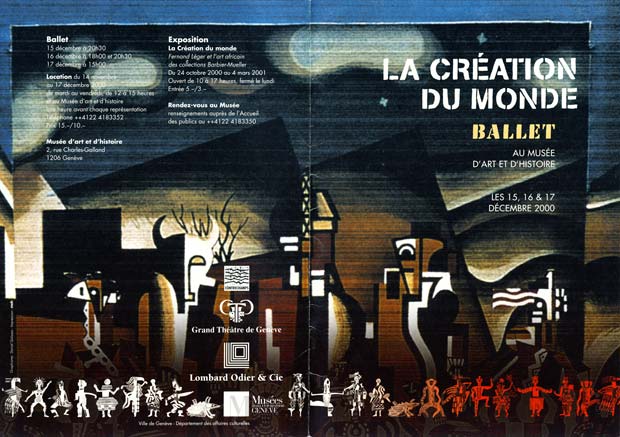

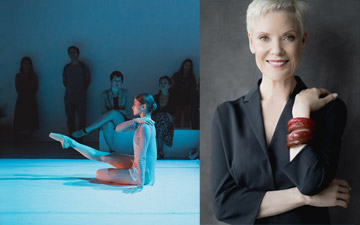

When Cynthia Odier of the Fluxum Foundation asked us to do La Création du Monde with the Ballet du Grand Théâtre, Geneva, in 2000, we realized that our task also was to make a collage. The occasion was an exhibition on Léger and African art of the Barbier-Mueller Collection at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, where we set the production on a purpose-built stage in the covered courtyard. Giorgio Mancini, a director of Geneva Ballet when we did Creation at the museum, engaged us in 2003 to restage the work at his new directorial post, Maggiodanza in Florence.

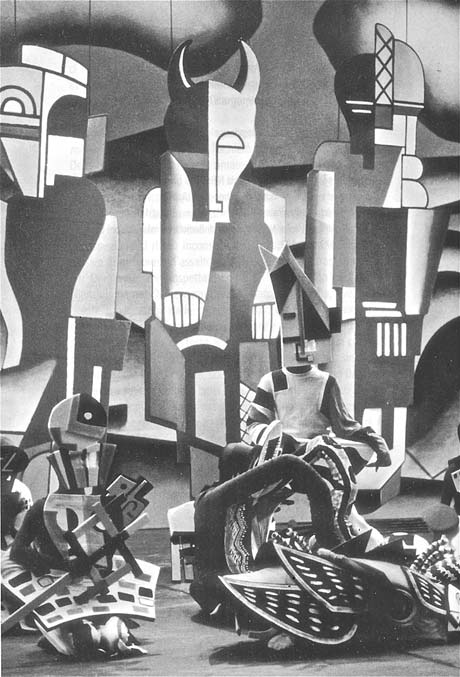

For the Nancy production with its current director, Petter Jacobsson, we have renovated the costumes with the atelier there and further developed the choreography. Jacobsson, a former dancer and director at the Royal Swedish Ballet, observed at a lecture we gave together in Nancy that the Ballet Suédois is a model for contemporary touring companies, like CCN Ballet de Lorraine, committed to new work and collaboration. He appreciated our perception of the 1923 work as a collage. Practically speaking, for our recreated collage, we needed more flexible and mobile elements. We worked with our costumier to find new materials that would maximize freedom of movement. A dancer from the original cast told us the company could not do “what Jean wanted” because the big Cubist structures in wood and heavy card were too cumbersome.

A further responsibility for us was suspension of disbelief: decoding the details of the designs and documents to follow clues to the original, wherever they might lead. La Création du Monde was not a political treatise about the hostilities the collaborators had managed to survive. Nor was it a work of art for art’s sake only. The ballet captures the heady mix of doubt, despair, daring and sassy confidence that marked the early twenties. But the spectre of the war keeps breaking through its surface. There were moments during our recent rehearsals in Nancy when we had flashbacks to documentaries about postwar Paris: as the Monkeys heaved themselves about with their arm-canes and an Insect dragged his carapace along the floor, we suddenly saw before us “mutiles de la guerre” who populated of the streets of French cities once the armistice was declared.

II. Europe As Seen from the Trenches of the Great War

La Création was a collage of the life the ballet’s collaborators saw all around them in Paris after the trenches – dynamic expectations edged with disillusionment about where Western civilization was headed. The subtext of the ballet is that love and creativity are always under threat. Part of what motivated “primitivism” in the arts, at least since Gauguin, was the critique of civilization which opting for a cultural “other” signified. In the case of La Création, “Africa”, a generalized concept of the epoch, served as that cultural alternative. Some measure of that seems to have prompted the enthusiasm of Cendras, Milhaud, Léger and Börlin for the Africa that they imagined. But the act of collage, reconfiguring reality, made a statement in itself about the need to change the established order of things.

According to the tale Cendrars chose for this ballet, the Creator destroyed his first attempt at a world, burning it all, because man, named Fam, who was very arrogant, had proved such a disappointment. The ballet is thus based on a second try at the grand plan. Characters are organized by gender and their place in the hierarchy of creation. Léger made the highest category not dancers but sculptures, the suspended Deities, moving laterally in and out of the dancing. Next come the Messengers of the Gods, male and female figures who are higher models of the human soul and body. Appropriately, they wear stilts in the shadow play prelude to the ballet. Characters who transit divine and human worlds are Magic People. These we had to interpret based on details of their costumes: the Egg and Water Witches and Wizards relate to organic creation; the Marimba Wizard and World Tree Witch relate to the forces of wood just as the Xylophone Wizard and Hatchet Witch relate to metallic forces. World Tree and Hatchet serve as midwives for the birth of the first man and woman. Next are the Fetishists, survivals of Fam energy, like the legions of Lucifer in biblical legend. Two Fetishists relate to nature and cosmos, Bird Man and Circle Man and two to human fabrication, Lattice Man and Block Man. We had to identify them, too, from the iconography of their designs. Last is the animal kingdom in its glory of colour and movement––Insects, Monkeys and Birds, free to roam their realms of earth and sky.

As part of the Création decor there is an articulated tree that rises from the ground, barren and charred, like the skeletal trunks silhouetted on the fields of France during World War I. Léger had been in the trenches and Cendrars was wounded in action. They knew from direct experience the spectral image we know from photographs and paintings of the period. “There was nothing great about the Great War except the scale of despair and destruction”, wrote Andrew Kelly in Cinema and the Great War. (1) Half the male population of Europe was sacrificed. Post-war disillusion was not just a European phenomenon. World War I was “the first officially global war”, as art historian Regina Mouton has emphasized, cataloguing U.S. race riots “that signalled the dissatisfaction of African-American veterans returning home…cast back into their previous condition of second-class citizenship.” (2) In Africa, she adds, “troops were “forcibly conscripted by the allied colonizers,” leading to the division of imperialist spoils by the League of Nations which split Germany’s African colonies between England and France. (3) The war to end all wars perpetuated itself. And the energy of Fam reasserts itself at every opportunity.

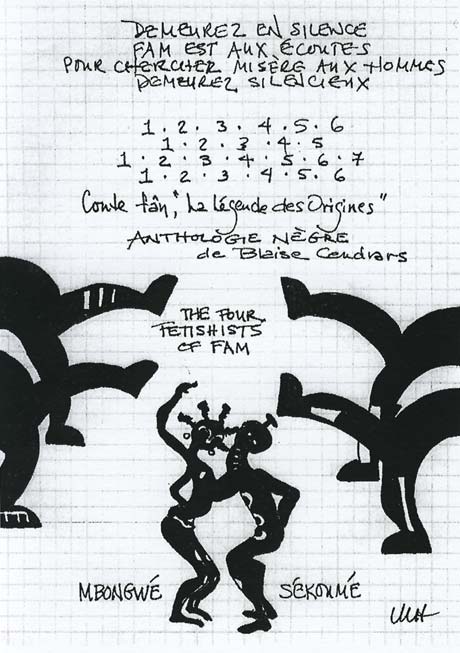

In La Création du Monde, as we learned from the wife of the ballet’s composer, a fragment of Cendrars’ tale is overheard by the audience. Although Madeleine Milhaud remembered this dramatic effect, it is not, to our knowledge, reported in any press. Maybe it was tried at a Ballets Suédois rehearsal and dropped. But we kept the idea, pausing the music momentarily for an offstage voice to recite a passage about Fam from the Anthologie. It happens just before the Fetishists come and steal the Branch, the symbol of humanity’s future, from the Human Couple, too distracted by their first love tryst to notice. The incantational rhythm sets the scene for the battle of the Branch that follows

Demeurez en silence

Fam est aux écoutes

Pour chercher misère aux hommes

Demeurez silencieux. (4)

Stay quiet

Fam is listening and ready

To inflict misery on mankind.

So keep still. (5)

III. Collage As Cultural Critique

The collaborators of La Création had about a quarter of an hour of stage time to make a statement: What did they want to say and why? Paul Nash’s iconic war painting of shelled trees shows dawn on the horizon and its title is “We Are Making a New World”. The 1923 ballet is solemn for much of the time, yet it is about hope. Creatures take form and emerge from a chaotic mass. Eggs, water and music seem to be the necessary ingredients for the Magic People to assist in creating the Human Couple. The dalliance of these primal lovers leads to the battle of the Branch, with the Monkeys joining the fight against the forces of Fam. But the Birds save the day. They fly in to seduce the Fetishists who quickly lose interest in the Branch. Love, or at least attraction to Cubist birds, makes the world go round.

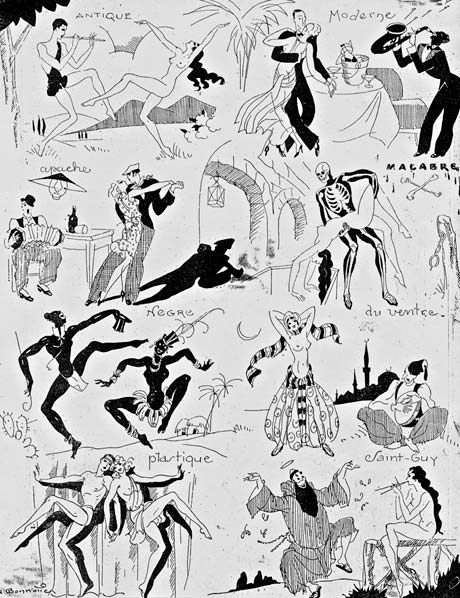

The postwar collage of La Création includes quotations from dance crazes like the “Char-less-ton”, as the French said it, and the Black Bottom. These “Negro dances” were already part of the Parisian landscape before the mid 1920’s. Börlin saved quotations of these fads for the upbeat Finale. Throughout the ballet there are references to show dancing, like steps for the Monkeys who imitate the “end men” in vaudeville.

A feature on La Création du Monde in Vanity Fair magazine just before the ballet’s New York premiere has intriguing clues about African dance elements of the collage. (6) Gilbert Seldes mentions that he “was present when the raw material of the choreography was being examined: a moving picture of certain African tribes in their native dances.” Having not yet “seen the result”, he gives no further details. Which dances we would ask, by which tribes, from which part of Africa? It is well-known that De Maré was a kind of dance ethnographer and shot film on his far-flung travels. Perhaps Seldes watched one of these with the collaborators during their preparatory work in Paris. There is little reportage about the steps danced in Création, but critics in France and New York noticed the lack of parody in the ballet’s use of “Negro dance.” Seldes also reports that films made by the French government include ceremonial stilt dancing and performers wearing “superstructure headdresses”, linking these sources to Léger’s designs.

Börlin, a protégé of Fokine and admirer of Nijinsky, was committed to expressive dance, which in those days was often called “plastique”, indicating free use of the torso and six o’clock kicks which ballet still considered risqué. The pas de deux of the couple was acclaimed for its expressivity and use of plastique. The music for the duet resonates with Milhaud’s knowledge of “Negro Spirituals”, and it was this section that George Gershwin echoed in Porgy and Bess––Gershwin was in Paris during the Création premiere in October 1923 but could also have seen the ballet in New York that December.

Börlin did not abandon classical dance altogether in his choreography.. Some of his works used the academic vocabulary throughout and, during his five years of service to the Ballets Suédois, he taught statutory company class every day, despite the pressures of choreographing at least twenty-five ballets and dancing almost a thousand performances as De Maré’s top box office attraction. Börlin paid homage to Nijinsky in several ballets and, according to Lundberg, there was a Nijinska “joke” in Création: the forward advance of toe-tapping Birds en pointe was a quote from Les Noces, which the Ballets Russes had premiered in Paris just a few months before, in June 1923.

IV. The Finale for Now

In 1923 Paris, and the collaborators on Création, had yet to see the big American all-Black dance shows like Blackbirds which would soon tour Europe. (7) Börlin’s work, especially Création, may have helped build the audience for these imports. Ironically, it was Josephine Baker and the Révue Nègre (which Diaghilev went to see in disguise) that supplanted Börlin in De Maré’s passions as an impressario. (8) By 1925 Börlin had been dismissed and “La Baker” became the star at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées.

Casting for the 1923 ballet was based on the structure of a jazz orchestra, Börlin imitating with the dancers Milhaud’s method with his instrumentalists. Every performer was a soloist, with duets and small groups providing the build-up for a full-scale, razzle-dazzle, all-in finale. But the ballet ends, as it begins, on a tone of greater gravity as the Gods and Messengers return and the couple dance a rather melancholy coda. It is a benediction of sorts, reminding the audience of all that has happened in a short time and evoking again the hope and disillusion that give the ballet its double edge, theatrically and politically.

REFERENCES

(1) Andrew Kelly, Cinema and the Great War. (London and New York, Routledge, 1997), i.

(2) Regina Mouton, “1919: From Exhibition to Appropriation and Its Inscription of Art in the Written Word” in Reading Between the Black and White Keys: Deep Crossings in African Diaspora Studies, ed. VéVé A. Clark (University of California, Berkeley: St. Clair Drake Forum, 2, Spring 1994), 155.

(3) Mouton, 155-156.

(4) Blaise Cendrars, “La Légende des Origines” in Chapter 1 `‘Légendes Cosmogoniques,” Anthologie Nègre (Paris: Editions Buchet/Chastel, 1919/1979), 11-17.

(5) Translation by Millicent Hodson.

(6) Gilbert Seldes, “An African Legend in Choreography”, Vanity Fair, New York, December 1923.

(7) Marshall and Jean Stearn, Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance (New York, Macmillan, 1968), 150.

(8) William Wiser, The Crazy Years: Paris in the Twenties (London: Thames and Hudson, 1983/1990), 157.

Such beautiful complex work! thank you for including the larger images.