Boston Ballet

Play with Fire: Sharper Side of Dark | Bella Figura | Rooster

Boston, Opera House

1 March 2012

www.bostonballet.org

Boston Ballet’s Play with Fire opened at the Boston Opera House recently with three contemporary ballets: Sharper Side of Dark by Jorma Elo, the company’s resident choreographer, Bella Figura by Jiri Kylian, and Rooster by Christopher Bruce.

Elo’s Sharper Side of Dark is a radical reworking of his 2002 ballet, Sharp Side of Dark, which he created for Boston Ballet early in his tenure. I’ve not liked Elo’s work in the past, finding it, like his titles, self-indulgent, hermetically private, and downright ugly. That earlier work has been based on an anti-ballet aesthetic of abrupt, disarticulated movements in which dancers look like spastic praying mantises on a bad drug trip.

But lord, what a sea change has taken place in this new work! Some ugly remains, but we should never forget Gertrude Stein’s observation that all truly original art looks ugly at first, which was certainly true for most early viewers of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism. Stravinsky’s early work, especially Rite of Spring, is another obvious example. But in Sharper, aggressively awkward movements are kept to a minimum: the ugly is reduced, and the residue now acts like a tonic of wit. And for the first time in Elo’s work, at least in my experience, we find a lyricism and beauty so profound they sometimes took my breath away.

The curtain rises on a woman standing on a bare stage with a black backdrop under a large circle of suspended spotlights. As the ballet proceeds a larger square of lights and three horizontal banks of spots appear, all combining in endless permutations. The woman performs some Elo spasms and then lures seven more dancers out of the darkness, her fingers wriggling like maggots. The women are dressed in purple corsets and black mesh tights, the men in black mesh T’s and black shorts. The dancers begin to move like machines coming to life.

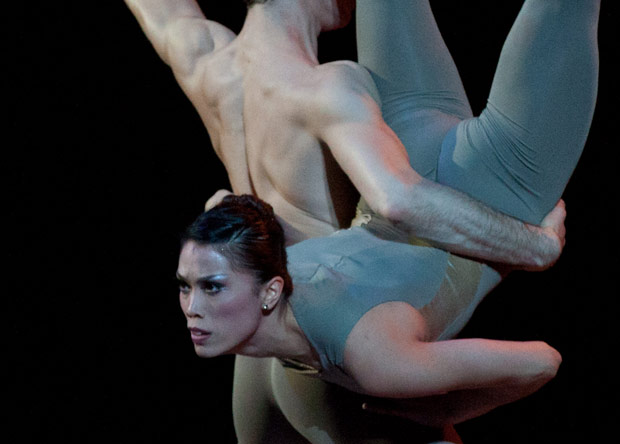

The music begins (selections from Bach’s Goldberg Variations) and its lyrical mood is immediately reflected in the choreography, which mostly changes into ballet mode. A short time later a woman lays her head on a man’s chest, as if listening to his heart, and their bodies undulate in unison. We’re suddenly in an entirely different world, one of achingly beautiful tenderness and intimacy. A woman faints in a man’s arms, and then a joyfulness appears, turning what in earlier work had been jerky tics into a form of play. The pas de deux between Kathleen Breen Combes and James Whiteside in part three is unquestionably one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen. In the final scene a man holds a woman in a suspended arabesque and you almost swoon until Elo undermines the vision by having them twitch their heads spasmodically. They end the ballet by descending to the floor in slow motion and collapsing into each other like a flower closing at dusk. The powerful human element I’ve tried to describe persists throughout the piece, making it one of the most memorable contemporary works I’ve seen in a long time. I suspect that like pasta and Tolstoy, Sharper Side of Dark is something I will never tire of. Please, Sir, We want some more.

The four couples, which included most of the best dancers in the company, were superb: Combes and Whiteside, Whitney Jensen and Jeffrey Cirio, Lia Cirio and Sabi Varga, Corina Gill and Paulo Arrais. The estimable Combes and Whiteside are a well-nigh perfect pair, while Jensen and Jeffrey Cirio have emerged as the two best dancers among the younger members of the company.

Bella Figura is Italian for making a good impression, though the relevance of that title to this ballet is as lost on me as the point of the nude male and female mannequins suspended in mid-air inside translucent boxes (coffins?) which appear as the curtain rises. Add the fact that the piece begins in silence (which is annoying since many in the audience haven’t returned to their seats after intermission) and that the women perform half the time bare-chested, and that in the final piece the stage is bracketed by two large flaming braziers, and you have one effect of the piece: arch perversity, a kind of post-modernist masturbation.

On the other hand, the score (a mélange of Lukas Foss, Pergolesi, Marcello, Vivaldi and Torelli) is highly effective and the choreography often visually arresting. Black curtains open and close, rise and descend, framing each part of the ballet and creating effects ranging from intimate to grand. A woman struggles to escape the grasp of someone holding her from behind the curtain. She screams silently and repeatedly a la Munch, placing her hand over her mouth each time. A dancer raises one shoulder and with her opposite hand pushes it back down, an image repeated throughout which becomes especially effective at the end when dancers push down each others’ shoulders. Women slowly emerge from their skirts as if being born underwater. Nine dancers appear in voluminous red skirts performing a Torelli concerto with hip bumps and hand flicks, like samurai at Versailles. So there’s a lot to look at and I’ve certainly enjoyed Bella Figura in the past, but this time it struck me as somewhat pretentious, perhaps because it paled by comparison with Sharper Side of Dark.

The final piece, Rooster by Christopher Bruce, was an unmitigated bore, although it did explain why we’ve never heard of Christopher Bruce before. Set to eight Rolling Stones songs, it’s performed by five men (roosters) and five women (chickens) who flirt, pair off, break up, and engage in the shenanigans of barnyard courtship. But early on you realize that although the men are individually costumed, the women are wearing identical short dresses. They’re also behaving like teenage tarts, shaking their fannies and strutting for the men who either manhandle or ignore them. A man lofts a woman over his shoulder and lugs her offstage caveman style. (When a woman slaps a man in the face, you want to cheer.) The whole thing is quite sexist, but when your seminal image is that of a rooster, how could it be otherwise?

The choreography is a smorgasbord of styles, all of them clichéd. Whenever a choreographer is reduced to having dancers writhe and roll on the floor, it usually means the tank is empty, but Bruce’s difficulty in inventing original choreography may also come from the sterile combination of ballet and rock music. Whether or no, I’m guessing that Rooster is the kind of light entertainment people are offered on cruise ships. It’s cheap fare, though it inadvertently reminded us of the difference between work of the first and second orders. With additional performances of Sharper Side of Dark, the ballet grew in power and beauty; the more I saw Rooster, the more it revealed itself as trivial and trite.

During each curtain call, someone placed a planter on the apron of the stage as . . . well, it must have been an offering to the dancers, right? But what were they supposed to do: wait until the curtain came down and flip coins? The final offering looked like pussy willows in terminal shock, but then no one would be disappointed to lose a coin toss for that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.